Racing the Bike, Perfecting the Robot: Introducing Étienne Samson

Posted on Aug 01, 2016 7:00 AM. 7 min read time

Technical Support Manager Étienne Samson's work at Robotiq is key to the company's plans to scale up production. But Étienne also lives a double life. He splits his time between training and motivating Robotiq's growing group of distributors, and training as a competitive cyclist and motivating his fellow cyclists as a team captain.

Robotiq was founded after lab-mates Samuel Bouchard, Vincent Duchaîne and Jean-Philippe Jobin decided to commercialize some of the mechatronic work they and their professor Clément Gosselin had created at Laval University in Quebec City. That was in 2008.

Today, Robotiq counts more than 30 full-time staff, and our Grippers and sensors operate in 40 different countries. We felt it was time to start telling the stories of our team members.

Robotiq’s Technical Support Manager Étienne Samson accepts that life is full of unexpected incidents. A man who deals with bicycle crashes seems to be in a good position to help those experiencing technology crashes. The trained engineer, trains as a competitive cyclist. He has raced in all kinds of countries, in all kinds of conditions and knows about finding oneself “in the middle of nowhere with a broken bike.”

Étienne works with engineers, customers and now a widening distribution network, addressing any and all qualms. He also reports back and consults with R&D to continuously simplify and improve Robotiq products. He addresses struggles with technology the same way he assesses bike damage or deals with an injury after a collision: he comes up with quick answers and practical solutions.

In his various roles with the company, he has helped improve the product and how it’s assembled, and understands the technology at a micro level. “I know all of our products so well that I can disassemble them with my eyes closed.” As a manager, he’s been increasingly working with people, training them to troubleshoot. He’s shifted focus from studying technological performance to now eliciting high-level human performance. It‘s another new challenge he embraces as he eagerly challenges those riding alongside him to also go beyond their personal best.

Meet: Étienne Samson, Technical Support Manager

In the 1980s, Étienne Samson saw only three career paths for residents of Quebec’s North Shore: fishing, mining or logging. But from an early age, the boy from Sept-Îles proclaimed that he wanted to be an engineer.

The proclamation did not emerge from divine inspiration but rather from the admiration of an uncle, who was a geological engineer. An employee with a mining company, the uncle would arrive in the region each month outside of the winter season to collect rock samples. From the age of 5 to 12, Étienne would visit him in his lab and watch him look for iron ore in those rocks.

The proclamation did not emerge from divine inspiration but rather from the admiration of an uncle, who was a geological engineer. An employee with a mining company, the uncle would arrive in the region each month outside of the winter season to collect rock samples. From the age of 5 to 12, Étienne would visit him in his lab and watch him look for iron ore in those rocks.

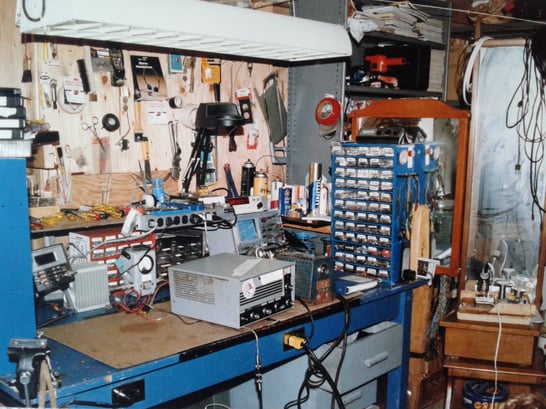

At the same time, Étienne’s father had his son rooting through junk yards and neighbor’s cast-offs for electronic parts that could be melted down for gold plating for various projects. An electronics technician, his father was also a keen hobbyist. One of the machines he built was a device to detect the movement of faraway moose and deer during hunting season, recalls Étienne. “He had a pointing device and a headset. You could point it a few 100 meters out and listen.” Étienne remembers using it instead for spying and listening in on conversations from neighbors.

Étienne would long to experiment and remembers sneaking into the workshop, only to break his father’s voltmeter on one of those visits. His father, always encouraging his son to explore, didn’t get angry over that incident. Étienne remembers as a child receiving a Commodore 64, a computer introduced in the early 1980s, with his father teaching him how to write computer commands for video games.

Given the freedom to explore, and having a scientist uncle who worked in both the lab and the field, and an inventive and encouraging hobbyist father, Étienne was propelled into full science mode. He joined a science club in school and began to have aspirations of not only engineering but also space exploration.

Given the freedom to explore, and having a scientist uncle who worked in both the lab and the field, and an inventive and encouraging hobbyist father, Étienne was propelled into full science mode. He joined a science club in school and began to have aspirations of not only engineering but also space exploration.

As a teenager, Étienne worked several part-time jobs to try and save up for a better computer. One of the worst jobs had him at the Sept-Îles docks, shoveling ice into bags in order for the fishing ships to keep their catches fresh. But that wasn’t the worst part of the job. When the ships returned days later, Étienne, who was about 14 at the time and small for his age, would be sent down with a rope. Once in the hull, he would have to shovel all that remained, with rotting fish in the mix. “I would be so stinky,” he recalls.

That work back then reinforces his credo of today: drudgery should be given to robots while the more creative and higher-level tasks reserved for humans. The experience also gave him boasting rights on a recent conference trip, where he and his colleagues were comparing the worst jobs they ever had – being lowered into a hull to dig out rotten fish won handily.

By university, his aspirations of becoming an astronaut were brought down to earth when he realized what the job entailed. “You need to be an engineer, a pilot and a doctor!” But his childhood dreams of working as an engineer remained strong. He pursued a degree at Laval University in Quebec City.

In his final year at university, he applied for an internship at a fledgling company called Robotiq, which at the time, in 2011, had four employees crammed into a small workspace above a dentist’s office.

CEO Samuel Bouchard interviewed Étienne at the university cafeteria. “He asked me what I knew about robots. I said I didn’t know anything. I was doing physics engineering. It had nothing to do with robots.” But he was given the internship, helped he believes by Samuel having completed the same engineering degree.

He began readying the company for its first line of 10 Grippers, putting together documentation and doing bench tests. He became one more body crammed into that space. “I was doing the assembly work, building the 3-Finger Gripper on our lunch table. I would work on that and, when it was lunch time, I would take everything away to have lunch. Then I would put back my stuff and work again at that table.” His internship would turn into a full-time job.

It was a heady time for Étienne. He was part of a new generation of robot builders that could see so much potential. “There were all these old companies that had built robots in the ‘80s and ‘90s. And nothing had changed in 15 years. We could see a lot of things to improve.”

But it was also a tough time. There was only enough money for one prototype on which to conduct tests, unlike the 20 the company has today. “We had ideas but no resources.” Bugs and updates seemed to outnumber new sales. But Samuel’s vision was strong and his connections with the industry would grow.

Those earlier challenges had no effect on Étienne’s drive. “I was learning so much. It was challenging, inspiring and we had so much to do.”

Not only was he being challenged in a new field, but he had taken up competitive cycling at around the same time that he began working with Robotiq. His first international race was the Vuelta Cyclista in Costa Rica, a 12-day approximately 2,000 km race. He was 27 at the time and was racing against guys who had been doing this since they were boys. He did not make it past the time trials. Three years later, he not only earned a spot to complete the race but placed in the top 50 of the final 120 riders, something he was proud of, considering the doping he witnessed. “You had the whole team of Costa Ricans and Colombians [cheating]. Before the time trial, they were all getting blood transfusions in front of us.”

Not only was he being challenged in a new field, but he had taken up competitive cycling at around the same time that he began working with Robotiq. His first international race was the Vuelta Cyclista in Costa Rica, a 12-day approximately 2,000 km race. He was 27 at the time and was racing against guys who had been doing this since they were boys. He did not make it past the time trials. Three years later, he not only earned a spot to complete the race but placed in the top 50 of the final 120 riders, something he was proud of, considering the doping he witnessed. “You had the whole team of Costa Ricans and Colombians [cheating]. Before the time trial, they were all getting blood transfusions in front of us.”

For Étienne, competitive cycling is all about the competition and not about simply keeping in shape. A competitive swimmer in high school and Cegep, he always loved that feeling a racer gets on the starting block. “For bike racing you have that for hours.” He says he loves the tension, feeling he’s on the edge and learning techniques that make him a smarter rider.

He trains on average 15 to 20 hours a week and appreciates that Robotiq has given him a schedule flexible enough to fit in both his training and competitions.

“I’m on a business trip and have my bike with me to keep training after the job is done in the evening.” Conversely, when he travels to a competition, he takes the time to do Robotiq work during off-hours.

He has enjoyed biking in Vietnam, San Francisco and even surprisingly in Arizona and Texas, two states he didn’t expect to be friendly to cyclists. His home province of Quebec, however, proved to be dangerous after one driver ran out of his car and attempted to beat him up. The man was recently convicted of the assault.

He has enjoyed biking in Vietnam, San Francisco and even surprisingly in Arizona and Texas, two states he didn’t expect to be friendly to cyclists. His home province of Quebec, however, proved to be dangerous after one driver ran out of his car and attempted to beat him up. The man was recently convicted of the assault.

But cycling has been good to him. He says it has given him discipline and helped him meet the unexpected. But both his intense training and robotics work leave little time for anything else. “I’m a single guy, living alone and have not been in my apartment for two months. I’m always on the road.”

Does he yearn for stability? “Of course, I want it, but not this year. I will want a family. And it will all come together at one point.”

In the meantime, his work calls him, as do customers with technical questions. He loves the fact that if he and a caller discover something that needs improving in the Gripper, he can easily prompt a change. “I can just walk in and speak to Jean-Philippe,” he says, referring to Chief Technical Officer Jean Philippe Jobin. “No one can believe how fast we can improve on our product.”

During his five years at Robotiq, he has moved from building products to being production engineer and from working in R&D to his current role as technical support manager. As the company grows, he will help staff get ready to scale up production.

“I will be more of a manager than an engineer. That’s a new set of skills,” he says, adding that it’s a big change from his “lone wolf” role of the last five years.

He says he will be the kind of boss that actually knows the work of his employees, having been in the trenches. He compares his new training role with that of a cycling captain. In that captain role, he loves bringing out in a rider something they didn’t believe they had and pushing them to a point he knows they can reach.

“I know that my teammates can do it but they don’t know it themselves.” He tells of one situation where he sent one rider who lacked

confidence out to attack. “I said ‘After the mountain, we’ll join you and break away from the peloton.’” After the cyclist was able to execute the plan he remembers the look on his face. “That’s when he was the most excited and proud of himself.”

“People will be afraid, but you just push them a little bit, motivate them and make sure they have what they need to succeed.”

Étienne Samson, a team leader on and off the road, and a boy who yearned to be an engineer now a robotics specialist helping to push Robotiq and take on its competition in an exciting industry race.

Leave a comment