He Ran Off to Join the Circus and then Brought His Creativity to Robotiq: Jean-Philippe Jobin's Story

Performing around the world as a circus performer and starting a robotics firm with two fellow students don't usually happen in one lifetime but Jean-Philippe Jobin has managed to have that kind of life. His curiosity and creativity come alive in Robotiq's R&D department, despite the lab having no unicycle.

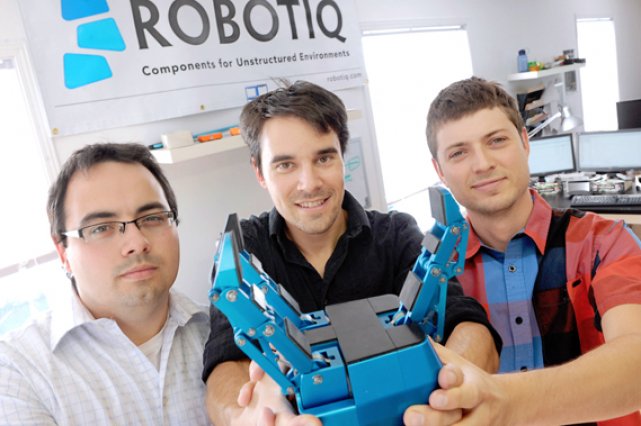

Robotiq was founded after lab-mates Samuel Bouchard, Vincent Duchaîne and Jean-Philippe Jobin decided to commercialize some of the mechatronic work they and their professor Clément Gosselin had created at Laval University in Quebec City. That was in 2008.

Today, Robotiq counts more than 30 full-time staff, and our Grippers and sensors operate in 30 different countries. We felt it was time to start telling the stories of our team members.

Robotiq’s Chief Technical Officer Jean-Philippe Jobin spent almost 25 years of his life as a circus performer – and he’s just shy of 39. From an early age, Jean-Philippe wanted to be an inventor but knew that wasn’t a bona fide profession. His circus work, which became his profession, took him around the world. But it also took a physical and emotional toll on him and led him back home to Quebec. Working on an Engineering Master’s degree, he found himself in that auspicious Laval lab with his two other visionary future partners talking about the same dreams.

Jean-Philippe brings to Robotiq an ability to connect to both engineers and clients, helping the former keep it simple so that the latter can easily use the technology. His circus days may be behind him now, but his natural agility, timing, teamwork and creativity have stayed with him.

Meet: Jean-Philippe Jobin, CTO

It was a fall day in Quebec’s Lotbinière region and 11-year-old Jean-Philippe Jobin spotted a boy riding a unicycle. He was fascinated and immediately asked his parents for a one-wheeler. That Christmas he did receive a unicycle as a present and wanted to take it outside and be just like the kid he had seen. But it was winter in his small rural town. So for the next three months, Jean-Philippe rode his unicycle around the family living room, managing to not break anything.

His dexterity with the unicycle led to a gig that summer on a riverboat, entertaining tourists. He would go on to take regular circus classes 30 km away, throughout high school. He would also go on to form a small circus troupe with other teens and tour around Quebec – a pork festival here, a corn on the cob festival there. A bigger circus troupe followed, this one earning invitations to festivals more prestigious than the ones celebrating pork or corn. He also helped found the École de cirque de Québec. He became a professional and toured around the world for audiences that could number 25,000 gasping spectators.

But let’s go back to his childhood. Jean-Philippe was also a kid whose curiosity and creativity led him to discover his technical side. “In the country we amused ourselves with everything and anything,” he says, recalling how he fashioned toys out of pieces of wood. He spent a lot of time with an uncle who was a builder and had parents who recognized his love for working with his hands.

“When I was young, if there was something broken, like an alarm clock or a VCR, my mother would give it to me and I would take it apart and try to repair it,” adding that most of the time he was not successful, but occasionally he would solve the problem. He was also inventive, recalling how he used a motor from a VCR to rig up a fan and a rudimentary robot arm attached to his bed, to help cool off his bedroom in the summer.

But he was not some young robotics nerd. Sure, he watched Star Wars like all the other boys his age, but he had other interests. Because his parents, both of them educators, wanted him to do well in school, he appeased them with a 70%-75% average; but he did not spend any more time than he had to on his education. Instead, he applied himself in two areas for which he felt passionate: circus and volleyball.

Throughout high school, Jean-Philippe would spend three nights a week practicing volleyball, and two nights a week and all day Sunday and Saturday training in circus arts, which included unicycle, juggling and acrobatics. When he entered Cegep (a post-Grade 11 junior college system in Quebec), he failed to make the volleyball team. “Okay, no problem, I thought. I’ll do more circus.”

He did just that, spending more time with Cirque ÉOS, a group of 20 people, aged 16-22, who were riding a wave of popularity for Quebec circus performers, thanks to the early fame of Cirque du Soleil. He and the circus toured around the world, visiting cities in the US, Europe, Japan and South America. In 1997, he entered Laval University in Quebec City, where he took up engineering. There, he would cram for an exam on a return flight or finish assignments backstage, spending little time on campus. In 1999, he quit his studies so that he could dedicate all his time to the circus.

Jean-Philippe was a circus star, cheered and feted around the world. He juggled, rode the unicycle, and performed feats of strength and intense control on the Chinese pole. With another performer, he held up the Russian Bar, which had acrobats tumbling through the air and landing on a four-inch-wide, 16-foot-long beam.

But in 2001, the international life of a circus star gave Jean-Philippe a sense of displacement. “I’d wake up in the morning and had to open the curtains to know exactly where I was in the world.” Spending over 250 days a year away from home was difficult on his relationship. And the physical exertion of a 10-show week, the constant impact on his back of holding the Russian Bar while acrobats jumped on it and having to perform in pain were all taking a toll. He was also feeling the monotony in the performances, which had no time for new creative input, and he missed the intellectual stimulation of university.

In 2002, he completed his undergraduate studies but still stayed involved in circus performance. In 2005, he combined his engineering skills with his knowledge of the stage for a Master’s project on a robotic performance space, where sound, lighting and stage-craft would be done with automation. Working out of Prof. Clément Gosselin’s robotics laboratory, he was meeting other students, including future Robotiq partners Samuel Bouchard and Vincent Duchaîne. Prof. Gosselin, the Canada Research Chair in Robotics and Mechatronics, had invented a robotic Gripper, on which the three students all worked.

With his Master’s work compete and the robotic stage finished, Jean-Philippe was wondering what he could do with his life. There was minor integrator work being done in Quebec, but if he wanted to do something more significant in robotics, he would have to go to Boston, Silicon Valley or Europe. But he wanted to stay in Quebec. Samuel was also wondering what he would do following university and had some ideas. “Prof. Gosselin said, ‘You two are talking about the same thing. Maybe you should talk to each other.’ So, we did.” Vincent was also part of the conversation.

The team did lots of brainstorming in Jean-Philippe’s living room, writing ideas on the windows. “We wondered about robots, where you take one by the arm and teach it. But we didn’t have the money at the time to develop a complete robot.”

Prof Gosselin gave them his blessing to commercialize his three-finger gripper and the three young men set about trying to convince industry that better end-of-arm tools could make their robots more efficient. Jean-Philippe saw a car analogy in this: “People were buying Lamborghinis but putting the cheapest tires on them.”

Robotiq was launched in 2008. Jean-Philippe remembers the difficult early days, emailing and calling people in the automotive and manufacturing sectors. “They would say ‘Okay, send me your CV and I’ll see what I can do.’ I’d say, ‘No, it’s not a job I want. I just want some of your time to make a proposal.’” He credits Samuel’s charisma in selling to those early customers. The company began to grow.

The three founders have complementary strengths and weaknesses and appear to respect those differences. “Sam is very visionary. He synthesizes things easily. He can do in one day what another can do in two days. He has a good flair for sales and marketing. And Vincent, he wants to know all the details. He really is our Chief Scientific Officer. We can sometimes bring up some crazy ideas to him and ask him what kind of technology we need to develop something.”

And his own contribution? “I think I bring creativity that’s very much on the ground, meeting challenges, getting results.”

His engineering knowledge allows him to speak the same language as his team of developers, while he never forgets about the customer’s voice. His goal is always to develop a product they can easily pick up and use without any knowledge of robotics.

Jean-Philippe makes decisions on when exactly a technology should be brought out, where the technical challenges lie and whether the company is capable of achieving it. He elicits feedback from beta testers and the people with whom he meets to make sure the product is responding to a need. He keeps an eye on production flow and performance, and tries to key in on the emotion and the aesthetic of the product.

“My role is to take technology and make concrete products that will be easy to use. And to make sure we’re a couple of steps ahead of the competition.”

His girlfriend Julie-Christine Racicot gave birth to their son Laurent on May 27. He joins sister Alice, 2, in the burgeoning family. No longer waking up in a hotel room in an anonymous city, Jean-Philippe reserves his weekends for the family and makes sure he’s home for dinner, even if it means having to work after the children go to bed.

The juggling, vertical pole gripping, trampoline flips and the unicycle tricks are not part of his everyday tasks but Jean-Philippe does see parallels in the two worlds’ creative potential. “It’s that excitement that I love, the moment when we see everything is possible; that it’s possible to create something.”

The juggling, vertical pole gripping, trampoline flips and the unicycle tricks are not part of his everyday tasks but Jean-Philippe does see parallels in the two worlds’ creative potential. “It’s that excitement that I love, the moment when we see everything is possible; that it’s possible to create something.”

Leave a comment