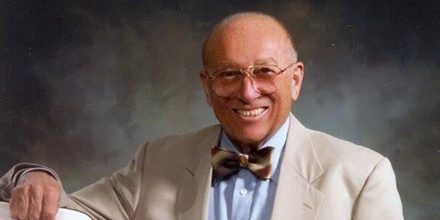

Joseph F. Engelberger - The Pragmatic Dreamer

Tributes for Joseph F. Engelberger have been pouring in from the robotics community since he died on the 1st of December this year. As an industry, we recognize that we owe a lot to the man who first brought robots to the manufacturing shopfloor, giving robotics a future in the world. But, what was it that sparked this seminal invention? Would robotics have been less successful if someone else had set the industry in motion? We take a look at Joseph Engelberger and ask what unique qualities made him justifiably "The Father of Modern Robotics”.

"The idea for [Unimate, the first industrial robot] came about … based on some of his dreams and aspirations from the writing of Asimov" said Engelberger's daughter, Gay, recently. "He just felt that [the robot] was the future."

The history of modern robotics seems to have been sparked by the imagination of Isaac Asimov. His three laws have driven the debate on robot ethics and his vivid depiction of autonomous servants have inspired generations of roboticists to further the dream of a robotic future.

One such dreamer was Joseph F. Engelberger, who died on the 1st of December at the age of 90.

Tributes from the industry and beyond have poured in for this "father of modern robotics”. The Robotics Industries Association provided an interactive timeline of his life. The EE Times paid tribute, as did the Robotics Business Review. The wider media also recognized his importance and several leading international newspapers published in-depth obituaries, including the New York Times in the US, The Telegraph in the UK and El Pais in Spain.

As the first person to bring robots to the factory floor, Engelberger was truly a pioneer. All the tributes to his life recognize his great business achievements and the effect they have had on modern manufacturing. However, few of them mention the unique quality that enabled him to jump-start the robotics industry. As I've been researching him, I've come to see that he possessed a rare balance between having a dreamer’s imagination and also being highly pragmatic.

He was able to dream of the possibilities of the technology, while remaining very realistic about its limitations. Having both these traits is not so common in robotics, where practitioners are often very practical, while dreamers and theorists are not pragmatic enough. As a field, we often focus too much on the technological development and not enough on the bigger picture, then when we are asked to "predict the future" we have a tendency to over promise. Joseph Engelberger was able to both dream of the future and be pragmatic at the same time, and perhaps that's why he succeeded where others might not have.

Fuelled by his love of Asimov's stories, Engelberger had a drive to see robots become a reality. He certainly wasn't one to "wait until the technology develops further" to put it into the world, which seems to be a trend in the robotics industry. His vision for robotic technologies made maximum use of their capabilities, but didn't try to solve difficult problems if a simpler solution made more sense. For example, in an interview in 2009 he was asked if his proposed low-cost healthcare robot could manipulate and break an egg for cooking. He replied, with refreshing pragmatism: "[Yes you could do it] but the chances are you're going to use the egg as a fluid, not as an egg. You don't have to go through all that agony of doing that because you can buy [cartons of pre-cracked eggs]. Just take the fluid and pour it out."

This practical attitude was reflected by the words of Frank Tobe, who gave his respects recently, saying that Engelberger "shared his passion for the utility of the product (and not just the process of developing it)."

However, Engelberger didn't start modern robotics all on his own. As he said himself when asked about people's initial reaction to the idea that a robot could build a car: "You gotta get someone who says "maybe that's true." General Motors happened to be a company that said "maybe that's true and if you build it we'll try it”. We built it and they tried it and they [the robots] worked."

In the preface of his book, Robotics in Practice, he also says he is indebted to: "Isaac Asimov who conveniently began his prolific writing career at a tender age with robotics as a theme (thus coining the name of the science and catching the fancy of this 1940's Columbia University physics major [i.e. Engelberger]). Then, one George C. Devol propitiously turned up at a cocktail party in 1956 with a tall tale of a patent application labeled Programmed Article Transfer."

Just as General Motors took a chance on the Unimate in 1961, Engelberger took a chance on Devol's invention five years earlier.

An Unlikely Partnership

George Devol was a self-taught inventor. During his lifetime he amassed over 40 patents to his name. The robot was the invention which got him into the Inventor's Hall of Fame; but he was also involved in the invention of the automatic door, a microwave oven and high-speed printers.

"It was, at first glance, an odd couple: The bow-tie-sporting Engelberger had degrees from Columbia University; Mr. Devol hadn’t graduated from high school." said an obituary of Devol in 2011.

Although some accounts say that the pair bonded over their mutual love of science fiction, according to Devol's daughter, Christine Wardlow, this was probably not the case. She said Devol "had no special love of the genre" and was a highly practical man, preferring "things that could be proven to those that could not". In contrast, Engelberger's vision came direct from the pages of science fiction, and many of his ideas were years from being provable.

Although some accounts say that the pair bonded over their mutual love of science fiction, according to Devol's daughter, Christine Wardlow, this was probably not the case. She said Devol "had no special love of the genre" and was a highly practical man, preferring "things that could be proven to those that could not". In contrast, Engelberger's vision came direct from the pages of science fiction, and many of his ideas were years from being provable.

"[Engleberger] liked to joke that at the cocktail party [Devol’s invention] sounded like a great idea and it sounded like a robot, just like in Isaac Asimov stories." said Engelberger's daughter, Gay.

They were both quite different people, but both had a burning desire to see robots succeed. However, although Devol was the more practical one with the invention, it was Engelberger who had the qualifications and the connections. Devol had not pursued higher education and instead chosen to go into business. Engelberger had an undergraduate degree in Physics and a Masters in Electrical Engineering from Columbia University, New York. At the time they met, he was the Chief Engineer in a railroad supply company, working in a department which made control technology for aeroplanes. When the war ended and the company requested he close the department, they broke out on their own to form Unimation Inc.

[The history of Unimation Inc is very interesting, but far too much to include in a small post like this. For an in-depth account, I suggest this account from George Munsen.]

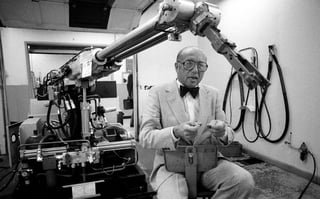

Robotics in Practice

One great example of Joseph Engelberger's character as a roboticist can be found within the pages of his first book, Robotics in Practice. Written in 1980, the tone of the book somewhat mirrors Engelberger's personality - the voice of a pragmatic dreamer.

Some parts read like an impassioned manifesto of why robotics are necessary for industry, with phrases such as "management often freezes in irrational fear of labour reaction and sheer conservative inertia" as he explains the challenges of promoting the adoption of robotics. In other sections, the book is packed full of practical guidelines on how to integrate robotics into a factory, ranging from specific applications (e.g die casting, spot welding, spray painting) to management and socioeconomic factors (e.g. organising to support robotics, robot economics and sociological impact of robotics).

He also takes time to flex his imagination and predict the "Future Capabilities" of robots. Some of these, like: rudimentary vision, tactile sensing and mobility have well and truly been accomplished since 1980. Others, such as: multiple appendage hand-to-hand coordination, general purpose hands and energy conserving musculature (energy efficiency) are making good progress, even if they haven't met his proposed deadline of the end of the 80s.

Throughout the book he remains highly pragmatic about the use of robots, saying things like: "No matter what the social benefits are, no matter how clever the technology, no matter how pretty the robot is to watch, every proposed investment in robotics has to pass the test of a critical financial appraisal".

His eclectic love of literature also shines through and the book is littered with cultural references, ranging from the poem The Man with the Hoe by Edwin Markham to HAL and R2D2 to the inhuman jobs portrayed in the movie Modern Times by Charlie Chaplin (which he compares to the "debilitating jobs" which robots can do in place of humans).

Perhaps the most charming aspect of the book is that Isaac Asimov himself wrote the foreword, which we can imagine must have pleased Engelberger. In this, Asimov echoes Engelberger's feelings about the importance of robotics. He says:

"Does a robot displace a human being? Certainly, but he does so at a job that, simply because a robot can do it, is beneath the dignity of a human being; a job that is no more than mindless drudgery. Better and more human jobs can be found for human beings - and should. […] There will be steady advances in robotics, and, as in my teenage imagination, robots will shoulder more and more of the drudgery of the world's work, so that human beings can have more and more time to take care of its creative and joyous aspects."

These "steady advances" continue to advance steadily, following the wave which began when the robotics industry was set in motion by Joseph F. Engelberger in 1961.

What do you think was Joseph Engelberger's most important contribution to robotics? Did you know him personally? Do you think anything should be added to our knowledge of him? What do you think is the most important trait of a roboticist? Tell us in the comments below or join the discussion on LinkedIn, Twitter or Facebook.

Leave a comment